Hello everyone and welcome back to my music newsletter Major Music Moments, in which I engage in some popular music discourse and attempt to put a scholarly spin on the whole thing!

First, I want to quickly thank the Music Journalism Insider for featuring my last post on hyperpop in their list of music scholarship last week. I was pleasantly surprised by the promo and feel humbled to be included among such great scholars and musicians as a very tired and stressed graduate student who still feels I have much to learn! Nonetheless, I appreciate it greatly and encourage all of my readers to subscribe to music journalism insider as well.

To return to the topic at hand, this week we will be departing from hyperpop to a different topic, but thankfully one that still involves a website that is simultaneously my worst enemy and the only thing that has kept me sane from 2020 until now: TikTok.

Like many, in the spring of 2020 I was uprooted from my life as a last semester music major, preparing for end-of-year concerts and my senior recital (which never happened, by the way!), and was placed in my home bedroom back in beautiful upstate New York with nothing but 98% of a bachelor’s degree and the TikTok app downloaded on my phone. In the app, I was bombarded with the short yet addicting song clips of youths dancing, making whipped coffee, and singing along to Say So by Doja Cat and Supalonely by Benee ft. Gus Dapperton. I, like many others, was sucked in by the addicting algorithm and the ability to pass time when it felt like the world was ending.

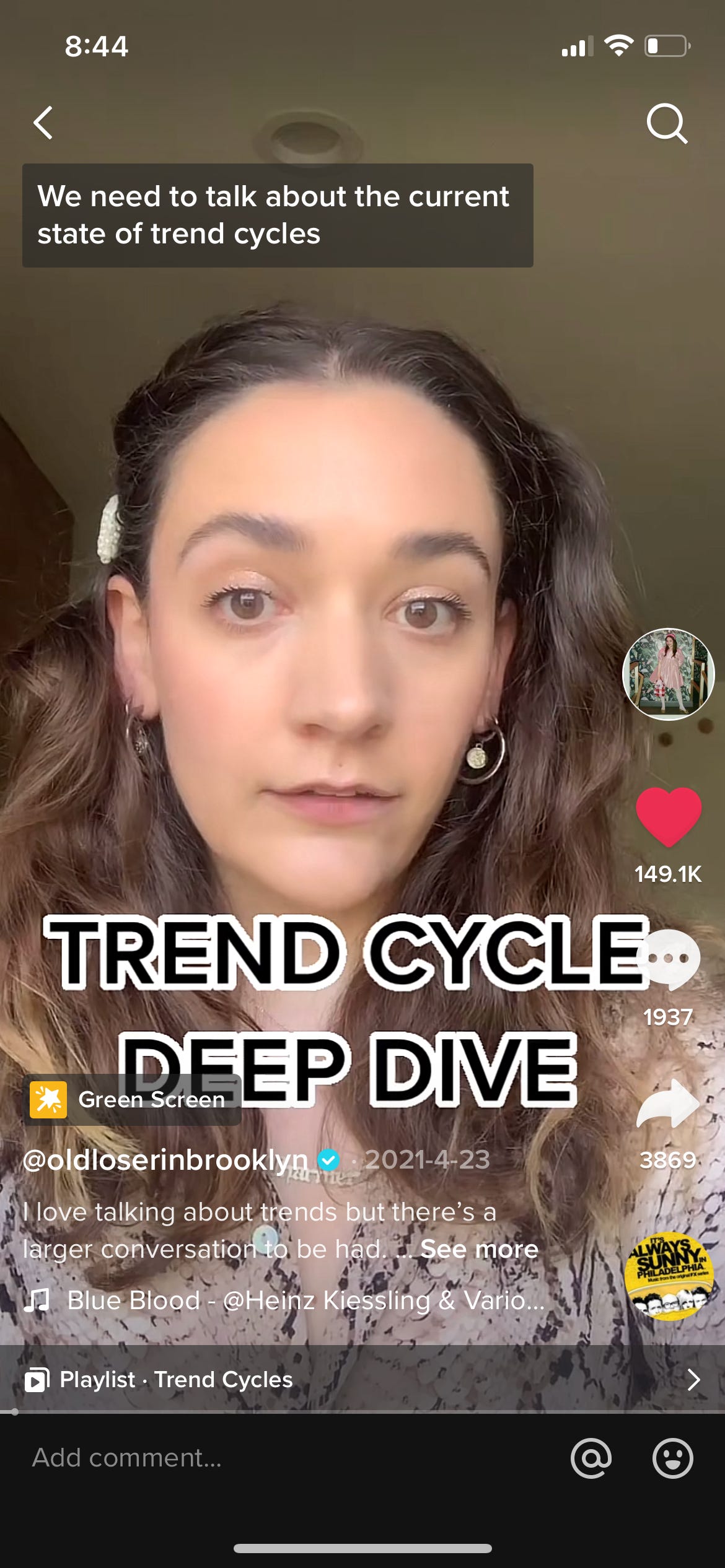

2 years later, much of this is the same, except I realized that maybe I could benefit from this content academically! At the end of one long day spent reading about musicological methodologies and trying to figure out what the heck “hermeneutics” means, I remember stumbling across a video by TikTok user and trend forecaster Mandy @Oldloserinbrooklyn. In this video, she discusses the inevitable speeding up of the trend cycle in fashion, and old styles getting recycled and then tossed faster than ever. Here is her initial analysis

“Increased trend turnover is fast fashion and capitalism’s dream state.” - Mandy Lee, @Oldloserinbrooklyn

An example of a trend cycle that Mandy is discussing likely derives from this table, known as Laver’s Law. James Laver was an art historian and fashion historian who created this classification to view given styles or clothing articles. This chart originally appeared in Taste and Fashion in 1937. This along with the concept of the “20-year trend cycle”, an idea prevalent in media studies, communications, and marketing along with many other fields, strengthen many of her observations and have great potential to open up a conversation about music.

Now, I am not a fashion expert by any means, but as an aspiring music scholar, I couldn’t help but wonder if this same issue is prevalent or being applied in the sphere of music as well, especially as we bring capitalism into the conversation. My thoughts flew to musicians I listen to obsessively now like beabadoobee, Soccer Mommy, and Snail Mail - Indie artists whose sounds, while great, are certainly not original by any stretch and derive sounds from myriad sources like 60’s folk, 90’s grunge, Elliot Smith, Stevie Nicks, Mazzy Star, and many others. Doja Cat, Silk Sonic, and Dua Lipa dominate the Billboard Hot 100 with definitively retro sounds and may evoke some memories of Earth Wind and Fire, Donna Summer, 80’s synth bands, and Motown in general. Silk Sonic specifically has seemed to have great success "bringing back" the bright, jewel-toned, decadent aesthetic of 70's Soul. The duo consists of Anderson .Paak and Bruno Mars seem to be suggesting a sense of nostalgia for this time and its music. To many, this music video can and should evoke an urge to escape to an era bygone.

Nostalgia is a bit of a strange word in regards to TikTok specifically. First of all, I ask you to understand that nothing is sacred. People have already decided to be nostalgic about 2016. Don’t believe me? Here is a young man who has collected the “best songs from 2016” and put them under a “sound” on TikTok. For those unfamiliar with the app, once you create a “sound” others can use this and make their video with it. Tell me why there are hundreds of people within my age range in the comments filled with pure nostalgia for 2016. And I can verify the accuracy of this because I was a freshman in college in 2016 and unfortunately participated in every single song and aesthetic involved in those linked videos. If that isn’t a sign of trend cycles and nostalgia being sped up on TikTok, I don’t know what is.

In general, though, my immediate reaction when people describe the return to '70s/80’s musical style or Y2K fashion as nostalgic is "Hold on- You guys weren't even alive for that. I wasn't even alive for that. So what are we even nostalgic for?"

Obviously, I am being a bit facetious and I do understand that we can appreciate aesthetics of the past without having been there AND that there may be some Gen X TikTokers who were, in fact, there. My question is: Are these trends that are prevalent in fashion and music indeed just a reflection of late-stage capitalism and overconsumption?

The reason why I bring capitalism into the mix is due to my recent reading of the book Music and Capitalism by Timothy Taylor, a professor of ethnomusicology at UCLA. Without simply reciting the whole book, which is a great read, I’ll throw out a few key points I jotted down after reading and relate them to my discussion of the trend cycle.

Most of what we are aware of as music today wouldn’t even exist without capitalism!

Taylor paints a great picture of our patterns of consumption through the years in the United States. From player pianos to Spotify, we come to understand how we got to where we are today. Simple realities like composers from the classical era simply wanting to both do what they enjoyed AND make a living show that things weren’t always this chaotic and that the idea of profiting from music was simply a reflection of music being a legitimate way to make a living. The values that capitalism encapsulates seem to pair very well with the direction that music was beginning to go in whether we liked it or not.

“There are complex ways that commodified music is invested with meaning and value by various social groups” - Timothy Taylor

This direct quote from the book addresses the concept of commodification, as emphasized by many critical theorists such as Marx and Adorno. Commodification refers to taking something, determining its value, and turning it into something to be purchased and sold. In Taylor’s book, he explains that music has effectively become a cultural commodity, rendering it no different from the exchanges of tangible goods that we are more familiar with, hence my various comparisons to fashion and trend cycles.

Music becomes less of an in-person participatory experience and more of something to be consumed, and the industry adores this idea. Itunes sales have merged into streams, and streams have become a measure of a song or artist’s success. Whenever you seek out a new artist on Spotify, you’re immediately bombarded with statistics about the artists, spilling the beans on their monthly listeners and number of plays, and top songs. Smaller artists tend to have lower numbers and often struggle to make money off of Spotify, ushering in an entire conversation about how streaming has affected artist pay - which Taylor also addresses in his book.

The introduction of digital technologies has really drastically changed music

And I cannot emphasize this enough. “Digital technologies” in this context simply refers to how we typically listen to music using technology. Vinyl on a record player, a cassette, a CD, opening up Spotify, and pressing play; All of these are the technologies that we might use on a day-to-day basis. Even the act of “private listening” i.e. the introduction of headphones and the walkman, fundamentally changes how we interact with the music that we listen to. In the past, music listening was perhaps more of a group activity. A family gathered around a piano, an opera performed in a theater, a marching band in the streets, now we can experience music in an almost undetectable way - A high school student with AirPods in and a hoodie pulled over their head to listen covertly during class. We’ve seen it all.

A real-life example of this was when I was leading a discussion about music for my undergraduate students and I brought up the topic of Disco Demolition Night in 1979 and showed them a short clip explaining it. When I asked them if they thought that something like this could happen today, in 2022, the answer was a resounding NO. When I asked a student to elaborate, they simply stated that people don’t care what other people listen to anymore because of how individualized everything is and that music is no longer physical; There’s nothing to burn and nothing to destroy.

Neoliberalism has taken advantage of these new technologies and therefore offers an illusion of freedom and creativity.

By now, you might be thinking: So what? We have access to every possible type of music at the click of a button, we can buy anything we want whenever we want and have access to it almost immediately. If we don’t like it, we simply don’t have to listen.

I think that what Taylor (and many others who study how music is intertwined with our values and practices) is trying to say is that music doesn’t exist in a vacuum and many of the external forces that impact the music industry should be examined critically. This is particularly important if there are cyclical patterns that exist within the music that could potentially become more and more noticeable as time goes on, and with globalization, ease of access, and social media how we listen continue to be altered by digital technologies, there’s no telling where we may end up in terms of musical trends, aesthetics, and practices.

To conclude this post, I think the last thing I’d like to add is that all of this isn’t to say that we need to stop recycling sounds and aesthetics. As their cyclical nature stipulates, it’s not the fault of any individual. Simply put, as long as we can continue to have the capacity to question trends, we’re better off than just ignoring these phenomena and letting them pass. By dismissing our actions as simply being “creative” or “free”, we’re not seeing the big picture. Though I don’t have the solution to the quick churning out and consumption of new tunes, styles, and aesthetics, I think we could benefit a lot from simply evaluating and meditating on this concept.

Of course, there are still a few questions that remain unanswered. Do music trend cycles directly parallel fashion ones? Are music trends also “speeding up”? What’s next to “come back” musically or what era will we draw from in the next 5 years? In the next decade? What are the potential consequences of capitalism’s impact on music? I don’t (currently) have the answers to all of these because this is a newsletter and not a thesis, but certainly, they are worth exploring for music scholars and patrons of the arts alike.

Okay, that's enough of that. Here are a few interesting things, people, and sources I have mentioned throughout this post.

Music Journalism Insider and their Twitter

Mandy Lee/@Oldloserinbrooklyn on TikTok and her substack Cyclical

Music and Capitalism: A History of the Present by Timothy Taylor

Podcast Episode on Taylor’s book hosted by Will Robin

Other things that I think are neat but not necessarily related

A documentary came out about black musicians in country music called For Love and Country

a TikTok Dunking on Wagner

An Album I Can’t Stop Listening To

MOTOMAMI by Rosalia

I hated this the first time I listened to it but it truly grew on me. I’ve seen it described as deeply experimental and complex. I don’t speak Spanish so I cannot confirm or deny part of that claim, but maybe people like it for the same reasons they like hyperpop! It’s weird, fun, danceable, and addicting.

A Song I Can’t Stop Listening To

Peur De Filles by L’impératrice

I came across this the other day and was reminded of Men I Trust, only… If they sang in french! It’s very funky and has a bit of a neo-soul vibe as well.

That’s all I have to offer for now, but be on the lookout for more posts this week and in the coming weeks!